Science fiction assumes many forms, but it generally has to feature some jump in evolution or gear. Novelty in tech or nature is key. Funny that the genre itself has mutated very little in the past century. You say the machines we build will try to replace us? Humanity will perish but our metal babies will preserve our legacy? From Karel Čapek to Kubrick to Black Mirror, storytellers have shown us fear in a handful of microchips. Sci-fi may be rarer in theater, but the burden of newness still rests on Jordan Harrison’s The Antiquities. A museum tour/reenactment by bodiless entities surveying half a millennium of human invention, this imaginative yet inert treatise moves, regrettably, like a glitchy CD player stuttering over the same track.

Harrison’s string of vignettes is one long object lesson stretching from 1816 Europe to distant dystopia. It’s a literal object lesson: a series of historic items—ranging from fire pits to telephones, computers and smartglasses—are now the fetishized, curated relics of a suprahuman artificial intelligence. Said godlike AI welcomes us manifested as two elegant, enchanting women played by (elegant, enchanting) Kristen Sieh and Amelia Workman. Draped in Regency chemises and vibrant shawls, they gaze at the audience with icy equanimity. “Look alive,” one urges us, and they mean it. In Harrison’s framing device, we spectators are immaterial beings engaging in “Late Human Age” cosplay. We pretend to have bodies and organs and brains, gathered in a virtual theater to puzzle over our skincestors, if you will.

The retrospective begins at night by Lake Geneva, as Mary Shelley (Sieh) and the very pregnant Claire Clairmont (Workman) lounge about with Percy Shelley (Aria Shahghasemi) and Lord Byron (Marchánt Davis), the latter Clair’s lover and father of her baby. Warmed by a fire pit, the young literati—along with Byron’s jaded doctor (Andrew Garman)—amuse themselves telling ghost stories. So far, so gothic. Suddenly Mary is struck by inspiration. “What if I used all the fire in the world, and made a baby that was beyond death,” she muses. “What if I used all the lightning in the sky.” Mary’s debut novel: It’s alive!

Already Harrison has distributed themes that run through the narrative: natural fecundity (babies) versus life-ish artifice—Frankenstein reanimating dead flesh; eventually, machines that think. The action flashes to 1910, where a boy (Julius Rinzel) is delivered by his poverty-stricken father into the care of two female factory workers, soon to face the inevitable mangling of his body parts in industrial gears. One of the ladies (Cindy Cheung, marvelously dry and droll) begins the scene contemplating her recently severed finger, once so handy in pleasuring her husband.

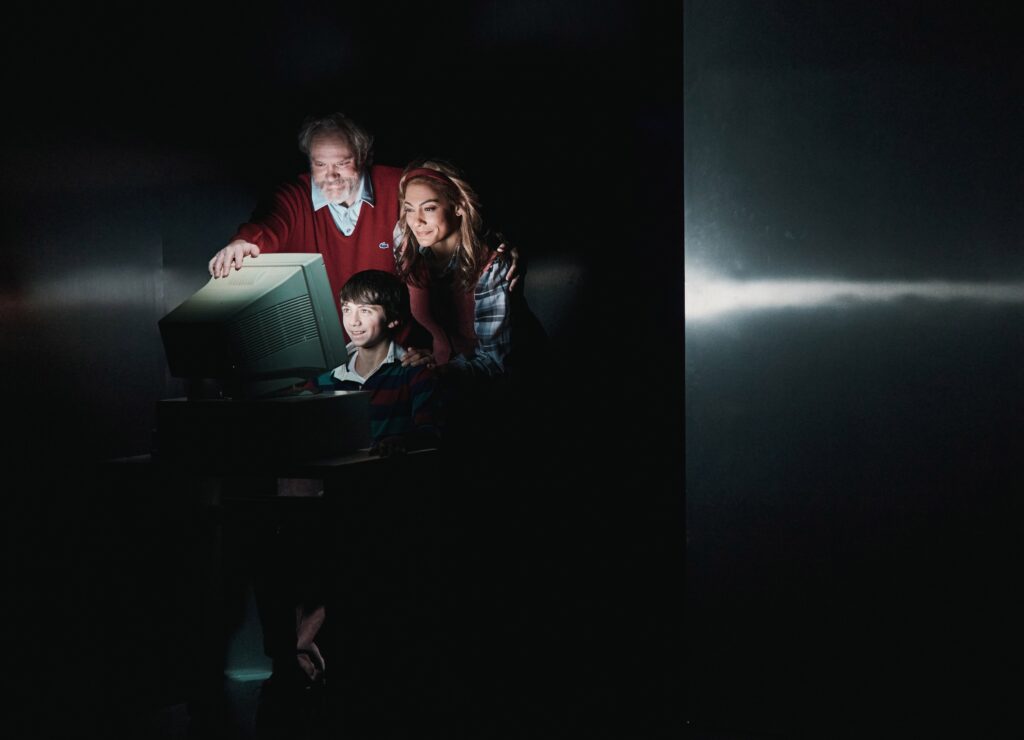

Each period “exhibit” is announced by the year flashed by LED light at the top of the proscenium: 1978, 1994, 2000, 2014 and beyond. We see the early days of robotics, home computers, the internet, cell phones, and Alexa-like digital assistants, woven through the lives of various characters we meet briefly, often at inflection points experiencing grief or dread. Harrison’s steady advance toward tomorrow is certainly effective at ratcheting up tension. It’s hard to ignore the tightening in your stomach as we bid adieu to 2023 and face a world already mapped by James Cameron. As a thought experiment, snapshotting the next 200+ years of human history as the rise of machines and the fall of civilization into neomedieval sparsity, Harrison’s apocalypse is ±±. Maybe we won’t end in fire or ice; it’ll be two bipeds in rags churning butter and arguing over whether to copulate.

However, when Harrison pauses the pageant and rewinds scene by scene, you begin to suspect there’s little more here than alt-historical cautionary tale. The playwright has shown human progress as a parable of folks creating toys that eventually supplant them. Does reversing the chronology shed further light? Not that I could see, it merely brings us back to where we began, on the beach with Mary Shelley, then our ethereal tour guides, then blackout. Armageddon pre-programmed. I kept trying to find a clue in the forwards-backwards motion. Was there a genealogical link from Clair’s baby in 1816 to those who followed, people who innovated robotics and AI? Or was this an elaborate writing exercise with spiffy dialogue, high-minded concerns, but little dramatic heft?

What’s more, there’s an inherent contradiction in Harrison’s world-building. If the shadowy beings in charge of this museum can recreate past eras with relative verisimilitude, why do they not grasp the function of a teddy bear or a cast for a broken arm, when these elements are realistically incorporated into skits? “If they are tools, we cannot ascertain their utility,” a voice ruminates in voiceover. “If they have religious significance, the gods they represent are long forgotten.” Had scenes churned with surreal, grotesque distortions of corporeality and physics (e.g., nightmare fuel AI videos), we might appreciate the Antiquarians’ struggle to understand human epochs. Language is another inconsistent head-scratcher. I find it hard to believe that renegade humans running from killer “inorganics” in 2076 would form such eloquent sentences as they do here, yet in a later period there’s an attempt to convey linguistic degradation.

It’s a pity: The Antiquities is a compelling concept and Harrison has a poetic, philosophical bent, but the execution lacks a certain audacity. One wonders what Caryl Churchill would have made of the premise (as with Love and Information, she’s master of the short, sharp shock). Not even a tightly directed cast and boldly designed production can overcome the sense that we’ve seen these tropes before on screens. David Cromer and Caitlin Sullivan share the staging chores, with a cherry-picked cast of all-stars. I’d watch Andrew Garman in anything, and his subtle variations on the avuncular but troubled father figure always draw you forward, as does the versatile Ryan Spahn as a gay, lonely robotics engineer, and the aforementioned Cheung as the mother of a dead college girl whose emotional withholding and moral disdain cry out for a whole drama. Tasked with leaping across aeons, the design team pulls off miraculous transitions: islands of life enter and vanish set designer Paul Steinberg’s silvery metal box, bathed in surgical lighting by Tyler Micoleau, haunted by Christopher Darbasssie’s evocative sounds, with actors garbed in transhistorical chic by Brenda Abbandandolo.

Harrison probed technology and human nature a decade ago with Marjorie Prime, also at Playwrights Horizons. A melancholy but wry family tragedy, Prime evoked a future in which senior citizens live with AI replicants of deceased loved ones. These digital caretakers learn, parrot, and eventually mangle the memories of their doddering wards. The earlier piece sustained complex, sympathetic characters in tighter focus. The Antiquities is more ambitious in scope, but by casting his net wide, Harrison fails to sink it deep enough, where the truly weird fish navigate their lightless, watery networks—probably for eternity.

The Antiquities | 1hr 40mins. No intermission. | Playwrights Horizons | 416 West 42nd Street | 212-279-4200 | Buy Tickets Here