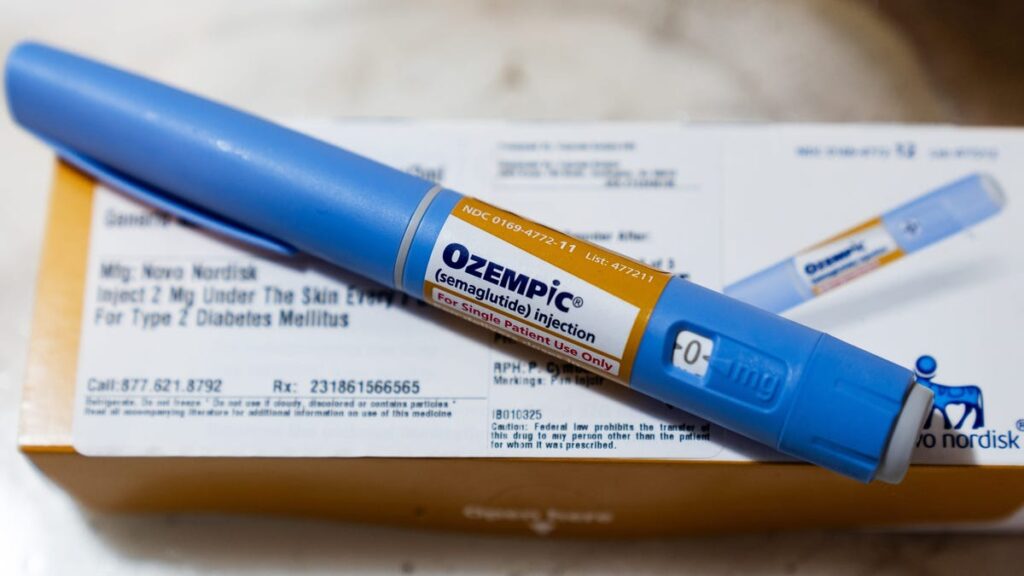

Will Ozempic, Wegovy be affordable in the near future?

Could the high cost of hugely popular weight loss drugs Ozempic and Wegovy be coming down in the near future?

Cheddar

Many Americans have turned to compounding pharmacies to get popular weight-loss drugs due to lack of availability or expensive retail price tags. But this option will soon close for consumers.

The federal government allows compounding pharmacies to sell copies of drugs when the medications are in short supply. Yet federal regulators recently declared the blockbuster weight-loss drugs Wegovy and Zepbound are no longer in shortage. That means consumers who use telehealth companies or medical spas to get less expensive, compounded versions will need to get their medications elsewhere.

That has panicked consumers such as Amanda Bonello, a Marion, Iowa, mother of three, who worries the supply cutoff will force her to buy the brand-name version of a drug she can’t afford. She takes a compounded version of tirzepatide, Eli Lilly’s drug sold under the name Mounjaro to treat diabetes and Zepbound for weight loss. The average retail price for Zepbound is nearly $1,300, according to GoodRx, a prescription drug discount provider.

“It leaves me up a creek without a paddle,” Bonello said. “It feels like we’re all on an island and Big Pharma has the only food source, and they’re letting everyone who can’t afford it starve.”

Industry groups that represent compounding pharmacies and suppliers have sued to continue selling these drugs. And patients have started an online petition to extend the time in which they can use compounded GLP-1, or glucagon-like peptide-1, medications. Alternatively, the petition requests the Food and Drug Administration authorize generic versions or encourage drugmakers to lower retail prices. The petition also seeks to compel health insurers to cover these drugs.

What’s status of compounded Wegovy and Zepbound?

Compounding suppliers and pharmacies will soon no longer be allowed to make and sell weight-loss drugs for the mass market. The federal government has authorized a transition period that’s already partly closed for compounded versions of Zepbound and Mounjaro. Consumers will have a bit longer to get compounded semaglutide, which is sold under the brands Wegovy for weight loss and Ozempic for diabetes.

In December, the FDA declared Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide was no longer in short supply. The FDA said pharmacies had until Feb. 18 to discontinue compounding, distributing or dispensing tirzepatide. Suppliers that produce batches of the drug and sell to others have until March 19 to cease distribution. The industry trade group Outsourcing Facilities Association sued the FDA in U.S. District Court in Texas and filed a motion seeking to delay such enforcement.

In a legal response to the industry trade group’s motion, the FDA urged the court to reject the group’s request. The agency argues rejecting the request would “maximize patient safety” and adhere to Congress’ intent to incentivize drug development while allowing compounding during temporary drug shortages.

Last month, the FDA said the shortage of shortage of Novo Nordisk’s semaglutide is over. Pharmacies must cease selling compounded semaglutide by April 22. Facilities that supply compounded semaglutide injections must cease distributing the drug by May 22.

I take compounded weight-loss drugs. What will my doctor or pharmacist tell me?

Pharmacists who supply compounded weight-loss and diabetes drugs already are discussing the situation with customers. Some aren’t refilling prescriptions. Others don’t want to start new customers on the compounded medications because they’ll soon need to switch to brand-name medications.

Within a year of discontinuing semaglutide, a group of 327 patients in the U.S., Europe and Japan regained two-thirds of weight lost while on the medication, one study found. The study said also said the patients were less healthy than they were while on the medication.

Jennifer Burch, who runs an independent compounding pharmacy in North Carolina, said she informs all her patients about how compounded drugs are available only when a brand name is on the FDA’s shortage list.

She fields questions from people who are interested in starting on compounded tirzepatide. With the drug shortage ending, she advises patients to not start taking compounded drugs if they won’t be able to access or afford the brand-name drugs.

“We try to make sure they know that up front,” said Burch, who is president of the Pharmacy Compounding Foundation. “We don’t want to pull the rug out from under them.”

Burch added some patients want doctors to write longer-term prescriptions so they can stockpile the compounded medication for up to one year. But doctors are reluctant to do that because they must monitor patients weight loss and overall health while on the medication, she said.

“I had a provider yesterday who said, ‘I’m really scared to write 12 months for a patient. They’ll come back to me and they’ll weigh 100 pounds. That’s not really what I want,'” Burch said.

The industry group Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding urged the FDA to approve the transition period for people taking compounded weight-loss medications to give them time to prepare for such as change, said CEO Scott Brunner.

Brunner said patients often must go back to their doctor or telehealth provider and get a new prescription for their weight-loss medications. This transition period gives pharmacies enough time to prepare for the change without abruptly changing patients prescriptions.

“This is all about continuation of care, assuring patients don’t experience some interruption of therapy,” Brunner said. “Abruptly ending these GLP-1 drugs can have potential health consequences.”

What’s being done to make brand name versions of weight-loss drugs more affordable?

Most large companies that provide health insurance benefits for workers and private insurance companies cover diabetes drugs such as Ozempic and Mounjaro.

But a survey last year by the benefits consultant Mercer said fewer half of large employers covered GLP-1 drugs for obesity. That means consumers often face large bills for drugs that retail for about $1,300 per month, before rebates or discounts.

While Congress has scrutinized pharmaceutical companies over the retail price of these medications, drugmakers have rolled out some discounted, direct-to-consumer options.

Last week, Eli Lilly slashed the monthly price for lower-dosage vials of Zepbound by $50 for consumers who pay cash via the drugmaker’s LillyDirect website. Consumers who buy a month’s supply of 2.5-mg vials will now pay $349 and 5-mg vials will cost $499. Lilly also announced higher dosages of 7.5 and 10 mg at monthly prices $599 and $699 respectively. Those higher dosage prices will be discounted to $499 per month for the first fill, as well as refills within 45 days.

Meanwhile, drug compounders are still pressing legal challenges to the FDA’s decision to declare the weight-loss drug shortages over. The Outsourcing Facilities Association sued the FDA on Monday over its decision to declare Novo Nordisk’s Wegovy and Ozempic are no longer in shortage. The industry group earlier sued the agency over declaration that Lilly’s tirzepatide was no longer in short supply.

In the tirzepatide lawsuit, the OFA filed a motion arguing the FDA’s shortage decision was effectively a new rule that requires a more comprehensive regulatory process. A federal judge has not yet ruled on the motion. The FDA said it won’t enforce its Feb. 18 deadline for compounding pharmacies to discontinue the drug until the court rules on the motion.

After the FDA declared the tirzepatide shortage over, Bonello said she planned to ask her doctor to switch her to compounded semaglutide. Now, she realizes that’s not a lasting solution, either.

Her workplace insurance plan covers GLP-1 diabetes medications but it doesn’t cover weight-loss medications. Although she has elevated blood sugar, she doesn’t have diabetes, even though other family members have been diagnosed.

Even with Lilly’s discounted price of $499 for the higher dosages announced this week, Bonello said she can’t afford that amount and still pay daily living expenses.

“That’s more than my phone bill and car insurance combined,” she said.